Equifinality & Multifinality - Many into one and one into many

The developmental psychopathology approach proposes that there are various, diverse pathways between early experiences and later outcomes. Things that happen, or don’t happen, can have different kinds of impacts, at different times or in different contexts, on different (i.e., individual) children. Diversity follows early adversity. And for this the principles of equifinality and multifinality are central.

Cicchetti, D., & Rogosch, F.A. (1996). Equifinality and multifinality in developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 8, 597-600 .

The concepts of mulitfinality and equifinality, explored in proper detail, can be very technical; although super-exciting and can even transform how you think about being in the world, if you like that kind of thing… But perhaps it is easier to just say:

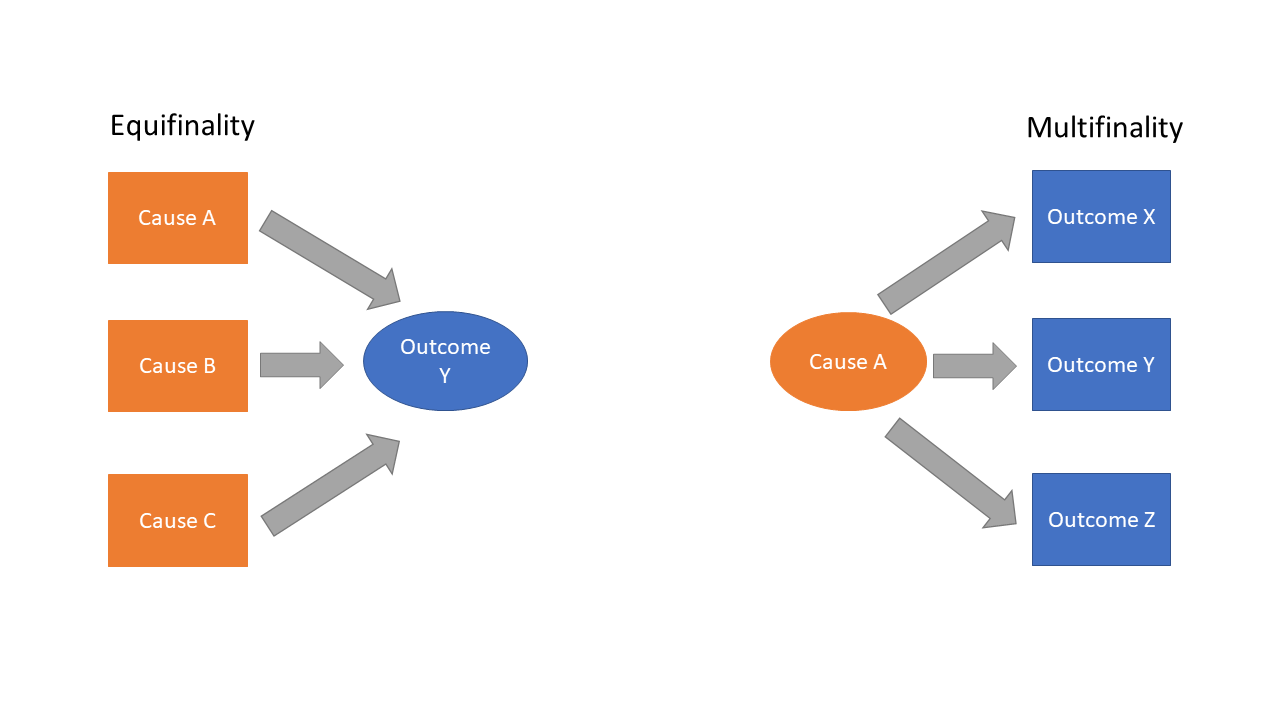

Equifinality means looking back that you can end up with an outcome Y [Y=varieties of wellness or pathology or whatever] via different routes or various pathways. Not everyone who ends up with depression has got there for same reasons or by following the same pathway. Or another way of saying it is that being well or unwell can arise from quite different mechanisms.

Multifinality means looking forward that a common kind of early experience A [A=traumatic event, or foetal toxin or whatever] can open up different pathways to different later outcomes. Not everyone who experiences a specific type of adverse event will end up with the same kinds of outcome, because they may well follow different pathways. So, what looks like an identical experience can typically lead to very different outcomes.

Applying equifinality and multifinality in practice

We can have as many causes in our model as we like. And as many outcomes. In the picture below, by way of example, it is 3. Three different types of potential cause (A, B, & C) leading to one outcome Y – an example of equifinality. Three different types of possible outcome (X, Y & Z) arising from a single potential cause A - an example of multifinality.

In the clinical work we do with children who have experienced early adversity these well researched and solid scientific principles seem to get lost along the way. Statements like “Children like her who experienced X will end up with Y” or “Children like him who are adopted have issues with A” just do not stand up to scientific scrutiny; especially the minute we start talking about individual children and not lumpen averages. No one parents an average, do they?

Early adversity and diversity

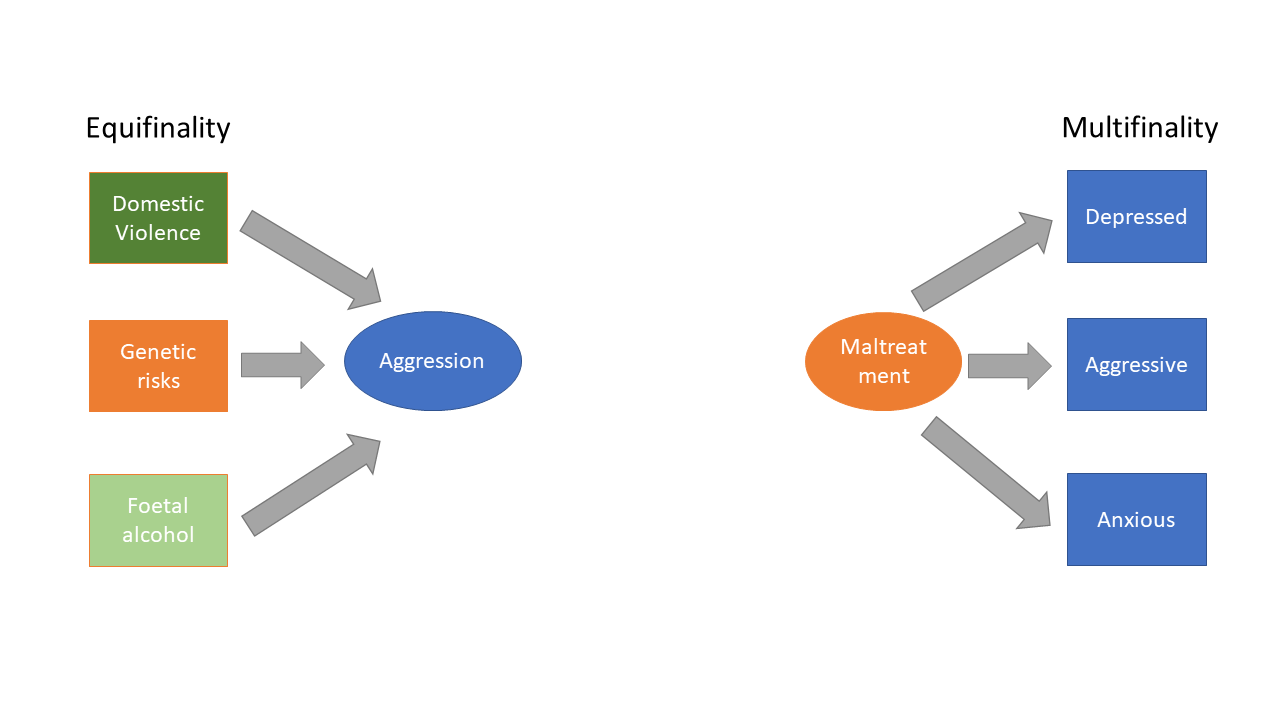

Below is a picture with some example causes and outcomes put in – hypothetical examples, not data driven probabilities. On the left-hand side, child aggression could be arising from different causes (there could be way more than the 3 here, of course), for some children domestic violence might be making a contribution; for others genetic risks; and for others exposure to foetal alcohol or other in utero experiences/toxins –> equifinality.

On the right we have multifinality, with early maltreatment leading to a range of different outcomes, here we have chosen depression, aggression and anxiety (in fact a recent huge study including data from over 11 million participants shows that early maltreatment has a series of relatively modest effects on a wide range of later disorders [Coughlan et al, 2022; 10.31234/osf.io/zj7kb], so we should reasonably expect way more than 3 outcomes as possibilities , and perhaps none on average very much more likely than any another…). Early adversities can be very diverse, when you start to look at them in detail, and so too their outcomes.

More diversity in early adversity and outcomes

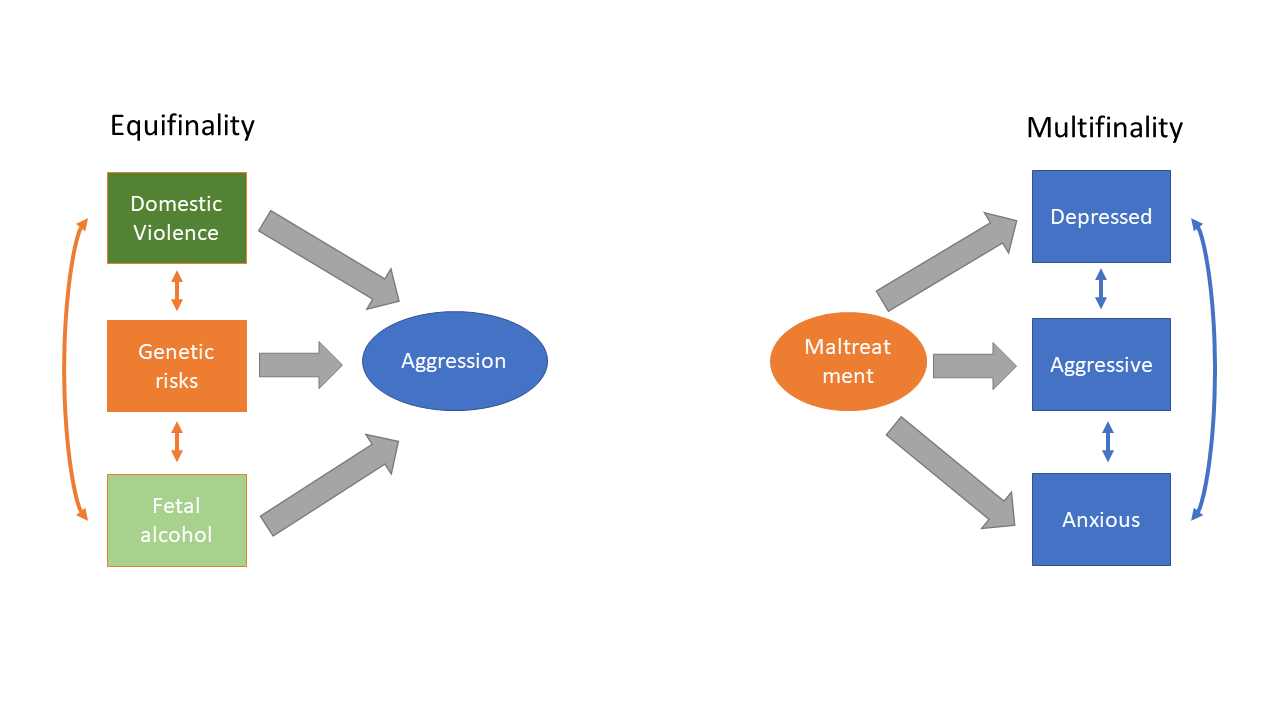

Often when we are considering children who experienced early adversity, we don’t have just one thing happening early on - bad things often accumulate and co-occur in higher risk samples; in research we might say they correlate or covary. Many different kinds of research bear this out. It is actually hard to do research on just on one type of early adversity in humans (although, maybe see the Romanian orphanage studies, e.g.. ERA or BEIP etc, for a very unique set of natural experiments that focused specifically on neglect in human infants).

Similarly, when thinking about negative outcomes, they too can co-occur; formally in mental health settings we might talk about comorbidity. There is a big question about how well services identify all the relevant comorbidities; or whether they get stuck on the most obvious presentation; or the one they just prefer, and then use that to explain everything else [technically we may refer to either diagnostic overshadowing or diagnostic masking depending on the specific process].

In the picture above, on the left, we might say that the single outcome of aggression is being contributed to by multiple factors, as it was in the first diagram. But here we allow some of these experiences to co-occur. So rather than just focusing on say exposure to domestic violence we have opened up our thinking to include other factors that might also be co-occurring. (Interestingly exposure to domestic violence might have its effect both prenatally in utero but also postnatally in terms of the child’s early caregiving experiences, amongst other ways; thinking about possible mechanisms of action is probably at a different conceptual level within a developmental psychopathology perspective than we are dealing with here, but could also be helpful for considering the individual child’s biopsychosocial formulation).

In the picture above on the right we can think about how early maltreatment is leading to various outcomes and in this instance the child might be depressed, aggressive and/or anxious. The model allows for early experiences to contribute to a range of problems which might be comorbid [co-occur]. Sometimes an aggressive child is seen first and foremost in terms of what can be observed, and the aggression tends to be more obvious and the anxiety and depression may not get noticed; so those issues become masked by the problem behaviour. Other children, especially those who are adopted or fostered, can get seen as having problems to do with trauma and/or attachment, and then other problems get overshadowed, becoming subsumed under those headings [and we have clear data on this, but that is for another day…].

Even more diversity in early adversity and outcomes

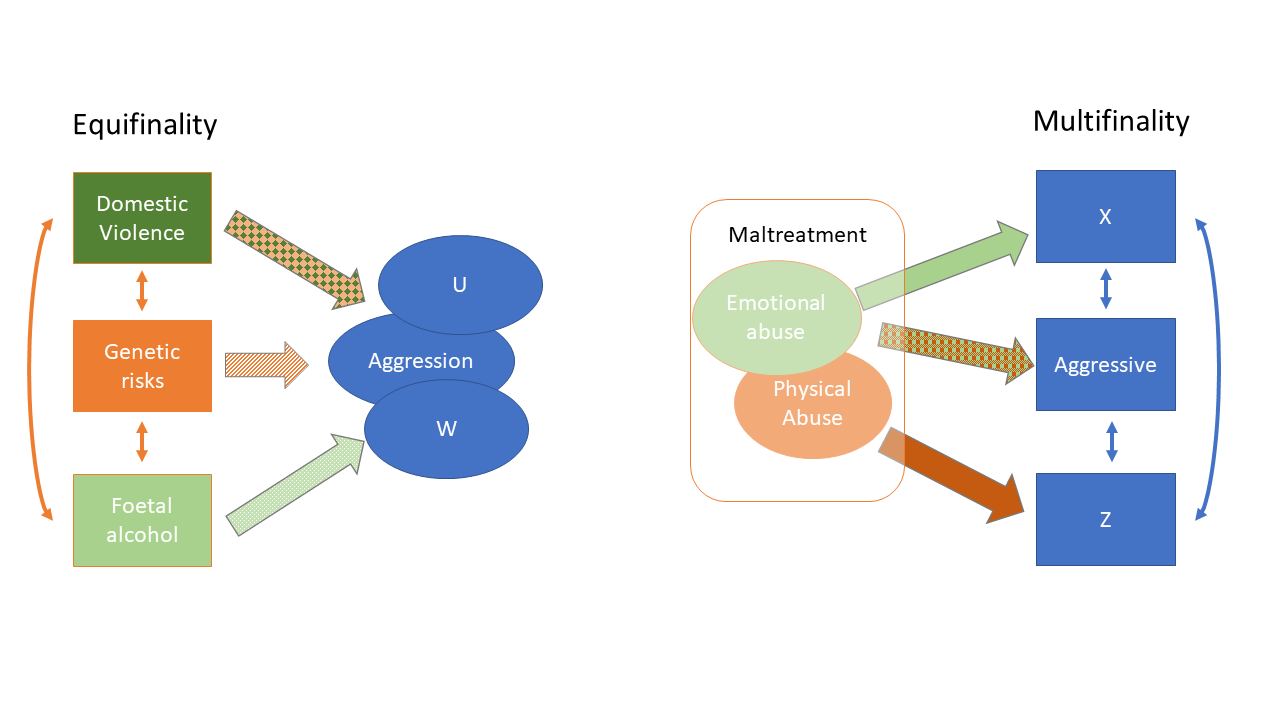

So it follows that for many young people with early adverse experiences there is the possibility of multiple co-occurrences of potentially causative events and various outcomes ….

In the picture above, looking at Equifinality on the left… many causes can co-occur with each other, but also diverse outcomes can co-occur and become comorbid. In the diagram here perhaps domestic violence and genetic risks co-occur to some extent and contribute to aggression and an additional outcome U. But also perhaps genetic risks and foetal alcohol exposure can co-occur and then contribute to aggression and outcome W. [U and W are placeholders, just to identify the process; they could be several things].

Looking to the right at Multifinality, we could split a potentially causal factor of ‘maltreatment’ into different sub-components with, say, more emotional abuse for some children and more physical abuse for others. In this hypothetical diagram we might start to think about a range of possible outcomes, aggression with or without additional outcome X or with or without additional outcome Z (of course you might also think about outcomes U and W… and many others too).

In fact, what we find with these two models is that as we start adding more and more possibilities the models begin to merge. In reality, the experiences associated with early adversity are highly diverse and the outcomes that you might expect to follow from this [highly diverse range of different kinds of adverse early experiences] are themselves highly diverse. Early adversity leads to a diversity in possible outcomes [can one ever say versions of that phrase too often? I think not]. And such diversity exists for good biological reasons. Biology tends to be big on diversity.

Early adversity leads to diversity in outcomes

What this means is that looking back to where problems came from with certainty is problematic for any individual child. Looking forward to predict with certainty where any individual child might be headed is also problematic. Really, when we meet a child who has experienced early adversity we should resist the temptation to oversimplify what is happening, and to avoid extracting one causal event or one definite outcome as adequately characterising their development. Each child needs to be considered as an individual. And be considered in terms of working hypotheses.

It does mean that figuring out what is happening for an individual child becomes complicated, and from an assessment point of view potentially time consuming and therefore expensive, which is a whole other kind of problem. But without an appropriate assessment how do you know what to do?

Keeping an open mind may prevent that child ending up in an over-simplified, conceptual cul-de-sac which doesn’t adequately describe their problems and which means they don’t get the range of potentially helpful interventions they need. Because, really, if your child has a complex history they may well need a range of interventions put together in an individualised package fitted to their specific presentation [and that package, or care plan, will need to be reviewed for effectiveness with outcome monitoring and potentially reformulated at various times over development…]. So we can see why many services prefer simplifications over complexity.